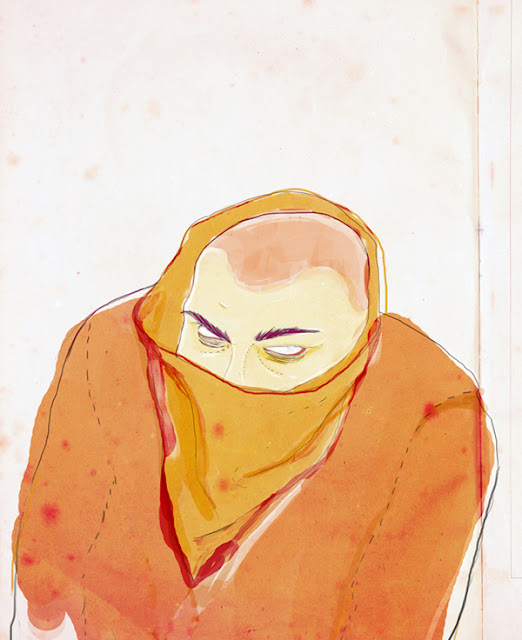

very relaxed guy

poniedziałek, 27 grudnia 2010

sobota, 25 grudnia 2010

wtorek, 21 grudnia 2010

poniedziałek, 20 grudnia 2010

niedziela, 19 grudnia 2010

poniedziałek, 13 grudnia 2010

niedziela, 12 grudnia 2010

poniedziałek, 6 grudnia 2010

sobota, 4 grudnia 2010

czwartek, 2 grudnia 2010

środa, 1 grudnia 2010

poniedziałek, 29 listopada 2010

The Cinnamon Shops - Bruno Schulz

The Cinnamon Shops - Bruno Schulz

illusttations

On Saturday afternoons, I would go with Mother for a stroll. From the duskiness of the hallway, we stepped at once into the sunbath of the day. Passers-by, wading in gold, were squinting in the glare as if their eyes were glued with honey; and their drawn-back upper lips bared their teeth and gums. And everyone wading through that golden day wore the same grimace in its scorching heat, as if the sun had bestowed upon all of its disciples the same mask, a golden mask of a solar cult. And everyone walking along the streets that day, young and old, every man, woman and child, met and passed by, hailing one another with that mask as they went, gold paint daubed thickly on their faces—they grinned to each other that bacchanalian grimace, a barbarian mask of pagan worship.

The market square was empty, and yellow in the heat, swept clean by hot breezes, like a biblical desert. Thorny acacias, springing up from the emptiness of the yellow square, frothed above it with their shining foliage, bouquets of graciously gesturing green filigrees—like trees on old tapestries. Theatrically twirling their crowns, those trees seemed to be stirring up a gale, so that they might show off by their pompous gesticulations the courtliness of the leafy fans of their silvered abdomens, like noblemen’s fox furs. The old houses, burnished by the winds of many days, were tinged with reflexes of the vast atmosphere, echoes and reminiscences of hues scattered to the furthest reaches of the coloured weather. It seemed that whole generations of summer days (like patient stucco workers scrubbing the mouldy plaster from old façades) had worn away a fallacious varnish, eliciting more distinctly day by day the houses’ true aspects, a physiognomy of the fortunes and the life that formed them from within. The windows went to sleep now, blinded by the radiance of the empty square; the balconies confessed their emptiness to the sky; open hallways were fragrant with coolness and wine.

W sobotnie popołudnia wychodziłem z matką na spacer. Z półmroku sieni wstępowało się od razu w słoneczną kąpiel dnia. Przechodnie, brodząc w złocie, mieli oczy zmrużone od żaru, jakby zalepione miodem, a podciągnięta górna warga odsłaniała im dziąsła i zęby. I wszyscy brodzący w tym dniu złocistym mieli ów grymas skwaru, jak gdyby słońce nałożyło swym wyznawcom jedną i tę samą maskę - złotą maskę bractwa słonecznego; i wszyscy, którzy szli dziś ulicami, spotykali się, mijali, starcy i młodzi, dzieci i kobiety, pozdrawiali się w przejściu tą maską, namalowaną grubą, złotą farbą na twarzy, szczerzyli do siebie ten grymas bakchiczny - barbarzyńską maskę kultu pogańskiego. Rynek był pusty i żółty od żaru, wymieciony z kurzu gorącymi wiatrami, jak biblijna pustynia. Cierniste akacje, wyrosłe z pustki żółtego placu, kipiały nad nim jasnym listowiem, bukietami szlachetnie uczłonkowanych filigranów zielonych, jak drzewa na starych gobelinach. Zdawało się, że te drzewa afektują wicher, wzburzając teatralnie swe korony, ażeby w patetycznych przegięciach ukazać wytwomość wachlarzy listnych o srebrzystym podbrzuszu, jak futra szlachetnych lisic. Stare domy, polerowane wiatrami wielu dni, zabawiały się refleksami wielkiej atmosfery, echami, wspomnieniami barw, rozproszonymi w głębi kolorowej pogody. Zdawało się, że całe generacje dni letnich (jak cierpliwi sztukatorzy, obijający stare fasady z pleśni tynku) obtłukiwały kłamliwą glazurę, wydobywając z dnia na dzień wyraźniej prawdziwe oblicze domów, fizjonomię losu i życia, które formowało je od wewnątrz. Teraz okna, oślepione blaskiem pustego placu, spały; balkony wyznawały niebu swą pustkę; otwarte sienie pachniały chłodem i winem.

illusttations

On Saturday afternoons, I would go with Mother for a stroll. From the duskiness of the hallway, we stepped at once into the sunbath of the day. Passers-by, wading in gold, were squinting in the glare as if their eyes were glued with honey; and their drawn-back upper lips bared their teeth and gums. And everyone wading through that golden day wore the same grimace in its scorching heat, as if the sun had bestowed upon all of its disciples the same mask, a golden mask of a solar cult. And everyone walking along the streets that day, young and old, every man, woman and child, met and passed by, hailing one another with that mask as they went, gold paint daubed thickly on their faces—they grinned to each other that bacchanalian grimace, a barbarian mask of pagan worship.

The market square was empty, and yellow in the heat, swept clean by hot breezes, like a biblical desert. Thorny acacias, springing up from the emptiness of the yellow square, frothed above it with their shining foliage, bouquets of graciously gesturing green filigrees—like trees on old tapestries. Theatrically twirling their crowns, those trees seemed to be stirring up a gale, so that they might show off by their pompous gesticulations the courtliness of the leafy fans of their silvered abdomens, like noblemen’s fox furs. The old houses, burnished by the winds of many days, were tinged with reflexes of the vast atmosphere, echoes and reminiscences of hues scattered to the furthest reaches of the coloured weather. It seemed that whole generations of summer days (like patient stucco workers scrubbing the mouldy plaster from old façades) had worn away a fallacious varnish, eliciting more distinctly day by day the houses’ true aspects, a physiognomy of the fortunes and the life that formed them from within. The windows went to sleep now, blinded by the radiance of the empty square; the balconies confessed their emptiness to the sky; open hallways were fragrant with coolness and wine.

W sobotnie popołudnia wychodziłem z matką na spacer. Z półmroku sieni wstępowało się od razu w słoneczną kąpiel dnia. Przechodnie, brodząc w złocie, mieli oczy zmrużone od żaru, jakby zalepione miodem, a podciągnięta górna warga odsłaniała im dziąsła i zęby. I wszyscy brodzący w tym dniu złocistym mieli ów grymas skwaru, jak gdyby słońce nałożyło swym wyznawcom jedną i tę samą maskę - złotą maskę bractwa słonecznego; i wszyscy, którzy szli dziś ulicami, spotykali się, mijali, starcy i młodzi, dzieci i kobiety, pozdrawiali się w przejściu tą maską, namalowaną grubą, złotą farbą na twarzy, szczerzyli do siebie ten grymas bakchiczny - barbarzyńską maskę kultu pogańskiego. Rynek był pusty i żółty od żaru, wymieciony z kurzu gorącymi wiatrami, jak biblijna pustynia. Cierniste akacje, wyrosłe z pustki żółtego placu, kipiały nad nim jasnym listowiem, bukietami szlachetnie uczłonkowanych filigranów zielonych, jak drzewa na starych gobelinach. Zdawało się, że te drzewa afektują wicher, wzburzając teatralnie swe korony, ażeby w patetycznych przegięciach ukazać wytwomość wachlarzy listnych o srebrzystym podbrzuszu, jak futra szlachetnych lisic. Stare domy, polerowane wiatrami wielu dni, zabawiały się refleksami wielkiej atmosfery, echami, wspomnieniami barw, rozproszonymi w głębi kolorowej pogody. Zdawało się, że całe generacje dni letnich (jak cierpliwi sztukatorzy, obijający stare fasady z pleśni tynku) obtłukiwały kłamliwą glazurę, wydobywając z dnia na dzień wyraźniej prawdziwe oblicze domów, fizjonomię losu i życia, które formowało je od wewnątrz. Teraz okna, oślepione blaskiem pustego placu, spały; balkony wyznawały niebu swą pustkę; otwarte sienie pachniały chłodem i winem.

czwartek, 25 listopada 2010

marry me - The Cinnamon Shops

When Father studied his great ornithological compendiums, browsing through their coloured plates, then out of them seemed to fly those fledged phantasms, filling the room with colourful fluttering—slivers of crimson, shreds of sapphire, verdigris and silver. At feeding time they comprised a varicoloured, surging patch on the floor, a living carpet which fell to pieces upon anyone’s incautious entry, rent asunder into animated flowers, fluttering into the air, to perch at last in the loftier regions of the parlour. A certain condor remains especially in my memory, an enormous bird with a bare neck, its face wrinkled and rank with excrescences. It was a gaunt ascetic, a Buddhist lama, with impassive dignity in its whole demeanour, comporting itself according to the strict etiquette of its great tribe. As it sat opposite Father, unmoving in its monumental posture of the ancient Egyptian gods, its eye clouding over with a white film which spread from the edge to the pupil, enclosing it entirely in contemplation of its venerable solitude, it seemed, with its stone-hard profile, to be an older brother of my father—the very same substance of its body, its tendons and its wrinkled, hard skin, the same dried and bony face with those same deep, horny sockets. Even Father’s long and thin hands, hardened into nodules, and his curling nails, had their analogon in the condor’s talons. Seeing it asleep, I could not resist the impression that I was looking at a mummy—the mummy, shrunken by desiccation, of my father. Neither, as I believed, had this astonishing resemblance escaped Mother’s notice, although we never pursued the topic. It was characteristic that both the condor and my father used the same chamber pot.

Not confining himself to the incubation of ever younger specimens, my father arranged ornithological weddings. He dispatched matchmakers; he tethered the enticing, ardent fiancées in the gaps and hollows of the attic. And he succeeded, in fact, in turning the roof of our house—an enormous, shingled span-roof—into a veritable bird’s inn, a Noah’s ark to which winged creatures of all kinds would flock from faraway places. Even long after the liquidation of the avian farm, that tradition regarding our house continued to be observed in the avian realm, and during the period of the springtime migrations, whole hosts of cranes, pelicans, peacocks and birds of all kinds would alight on our roof.

Nie poprzestając na wylęganiu coraz nowych egzemplarzy, ojciec mój urządzał na strychu wesela ptasie, wysyłał swatów, uwiązywał w lukach i dziurach strychu ponętne, stęsknione narzeczone i osiągnął w samej rzeczy to, że dach naszego domu, ogromny, dwuspadowy dach gontowy, stał się prawdziwą gospodą ptasią, arką Noego, do której zlatywały się wszelkiego rodzaju skrzydlacze z dalekich stron. Nawet długo po zlikwidowaniu ptasiego gospodarstwa utrzymywała się w świecie ptasim ta tradycja naszego domu i w okresie wiosennych wędrówek spadały nieraz na nasz dach całe chmary żurawi, pelikanów, pawi i wszelkiego ptactwa.

niedziela, 21 listopada 2010

wtorek, 16 listopada 2010

poniedziałek, 8 listopada 2010

sobota, 6 listopada 2010

niedziela, 31 października 2010

czwartek, 28 października 2010

wtorek, 26 października 2010

czwartek, 21 października 2010

środa, 20 października 2010

sobota, 16 października 2010

Subskrybuj:

Posty (Atom)